From 3/5 to 1 – Tues Sept 27

by admin - September 22nd, 2016

Course update: I’ve added two new sections in Blackboard – an archive of the response paper prompts, and a list of calendar events outside of class which can be used for extra credit.

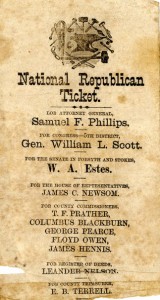

For Tues 9/27: When the Constitution was first established and ratified, slaves were counted as less than full persons for purposes of representation in our government, and enjoyed none of the legal privileges or rights of citizenship. To be precise, each was 3/5 of a person. This “compromise,” as it is often called (and is that a good word for it, really??), was created (of course) without the consent or input of enslaved people, as a way to balance power and apportionment between slave/free and large/small states at the time of the Constitutional convention.

So: when, and how, and why, did blacks first become free and then become counted as full people under the Constitution? Our discussion on Tuesday 9/27 will focus on Good Citizen, Ch. 3 and Right to Vote, Ch 4. Please take careful notes and/or bring the books to class. Also, please study for your re-take of the U.S. Citizenship Exam which we will do in class.

So: when, and how, and why, did blacks first become free and then become counted as full people under the Constitution? Our discussion on Tuesday 9/27 will focus on Good Citizen, Ch. 3 and Right to Vote, Ch 4. Please take careful notes and/or bring the books to class. Also, please study for your re-take of the U.S. Citizenship Exam which we will do in class.

Due in class: A 2-3 page double-spaced, printed response paper based on the prompt distributed in Thursday’s class. If you attended the Profiled film on Thursday or the conference on Civic Engagement in Higher Ed on Friday for extra credit, your write-up paper is also due.

What were strategies (political, religious and otherwise) used to challenge the legality and morality of slavery? How successful were those strategies? How did they compare with early strategies for women’s suffrage?

Was granting the vote to black freedmen in the South during Reconstruction part of the general trend toward widening of the franchise, or an exception to it?

What did the 14th Amendment accomplish? What did it NOT accomplish?

Why is the story of the passage of the 15th Amendment a “strange odyssey”?

How were the experiences of white women and black men connected during Reconstruction? Where did this leave black women?

Describe the “redemption” of the South. In what sense was it redeemed?

After being enfranchised, how were African-Americans then (legally and otherwise) disenfranchised?

Given this history, what is the meaning of legal “personhood” in 19th century America, and how is that different from citizenship?